- 2018 was the warmest year on record for the planet’s oceans, and the fourth-warmest year ever in terms of surface temperature.

- Scientists are discovering that melting in Greenland and Antarctica is occurring much faster than they previously thought.

- These changes could spell disaster for coastal economies in the form of sea-level rise and more frequent (and intense) natural disasters like hurricanes.

- If worldwide carbon-dioxide emissions aren’t curbed significantly – and soon – Earth might be almost unrecognizable by the year 2100.

We’ve already gotten a series of one-two punches on the climate change front this year: Ocean temperatures broke records, Arctic and Antarctic melting reached unprecedented rates, and extreme weather swept through the US.

An increasing number of people are concerned about the issue of climate change, as evidenced by recent worldwide climate strikes and efforts by US lawmakers to enact new environmental legislation.

On April 22, the world will celebrate the 49th annual Earth Day, a global event that more than 1 billion people participate in across 192 countries. This year, Earth Day organizers are attempting to call attention to one particular consequence of a warming planet: the skyrocketing number of flora and fauna species that are becoming vulnerable to extinction.

Read More: 12 signs we’re in the middle of a 6th mass extinction

If we hope to limit some of these impending extinctions, along with the other disastrous effects of climate change, we must make drastic cuts - and soon - to greenhouse-gas emissions from energy production, transportation, industrial work, farming, and other sectors.

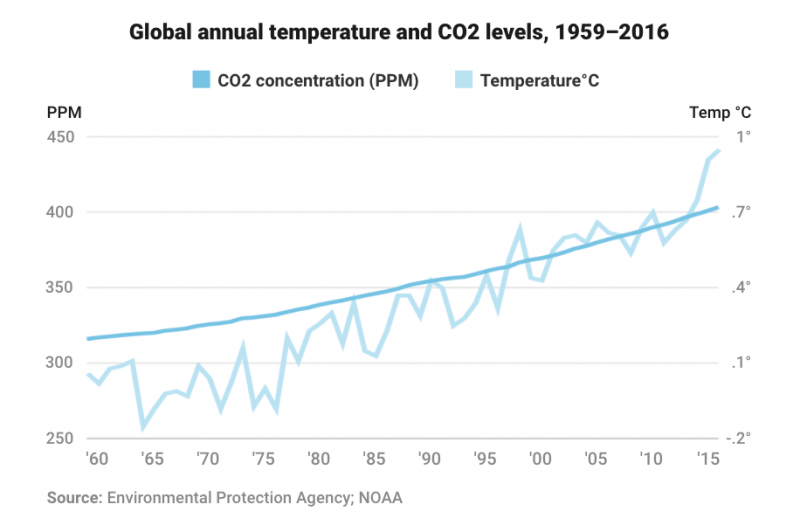

According to the most recent report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global temperatures will likely rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 if warming continues at the current rate. Staying under that threshold was the optimistic goal set in the Paris climate agreement.

But even if carbon emissions were to drop to zero tomorrow, we'd still be watching human-driven climate change play out for centuries.

"There's no stopping global warming," Gavin Schmidt, a climate scientist and the director of NASA's Goddard Institute of Space Studies, previously told Business Insider. "Everything that's happened so far is baked into the system."

Here's what the Earth could look like by 2100 in our best- and worst-case scenarios.

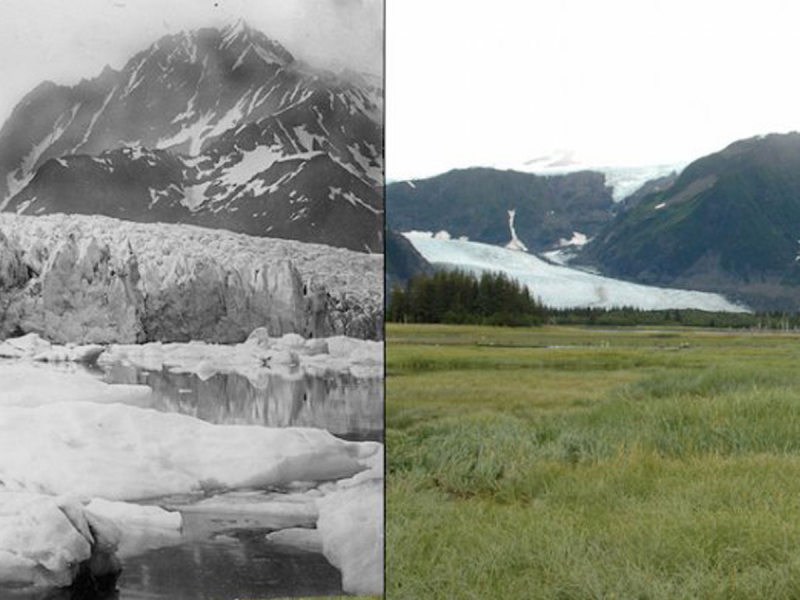

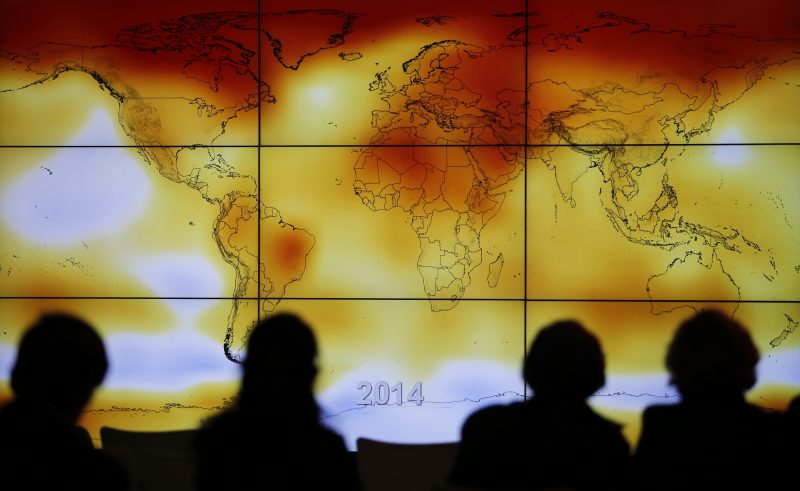

To understand where we're headed, we must first assess the changes we're already observing. Since 2001, we've seen 18 of the 19 warmest years ever.

The planet's oceans absorb a whopping 93% of the extra heat that greenhouse gases trap in the atmosphere. Last year was the warmest year on record for the oceans.

By the end of 2012, Greenland had lost more than 400 billion tons of ice — almost quadruple the amount of loss in 2003. Except for a one-year lull between 2013 and 2014, those losses continue to accelerate.

In the 1980s, Antarctica lost 40 billion tons of ice annually. In the last decade, that number jumped to an average of 252 billion tons per year.

Source: Nature

Oceans also absorb more than one-third of all the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which causes them to become more acidic. We are already seeing the devastating effects of that elevated acidity in the form of severely bleached coral reefs and dying marine life.

Source: International Geosphere-Biosphere Program

Warmer water is contributing to more frequent and intense hurricanes. Such storms are observably rainier than they were in the past, which causes more severe flooding.

Sources: Business Insider (1, 2)

A warming planet also leads to extreme weather, both cold and hot. A 2017 study found that the frequency of polar-vortex events has increased by as much as 140% over the past four decades.

Source: Business Insider

Climate change is also leading to more warm, dry days in regions with a risk of wildfires, like California. In November 2018, the most deadly and destructive wildfire in the state's history — the Camp Fire — started during what is typically the rainy season.

Sources: Business Insider (1, 2)

Schmidt is fairly pessimistic about our ability to keep temperature-rise under the threshold scientists consider safe. "I think the 1.5-degree target is out of reach," he said, adding that we may blow past that by 2030.

But Schmidt is more optimistic about keeping temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius. That's the upper threshold of temperature rise that the Paris climate agreement aimed to avoid at all costs.

So let's assume — optimistically — that we land somewhere between the targets of 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius of temperature rise.

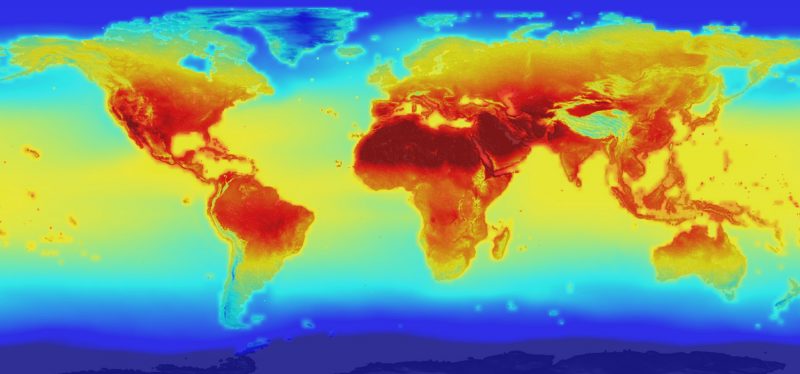

Even if we curb emissions, summers in the tropics would see a 50% increase their extreme-heat days by 2050. Farther north, 10% to 20% of the days in a year would be hotter.

Source: Environmental Research Letters

Summer temperatures in the US will keep rising, and much of the western and central US will see a reduction of soil moisture, which exacerbates heat waves. By 2100, extreme heat days (one-day events) that typically happened once every 20 years are projected to occur every few years.

Source: NASA

Some regions may benefit from climate change. San Diego, for example, could see an increase in "mild weather" days. But that city is close to the coast, so it's susceptible to sea-level rise. Plus, such cases are exceptions rather than a rule.

Source: Business Insider

Even in an optimistic scenario, temperature anomalies — how much the temperature of a given area deviates from what would be "normal" in that region — would swing far more wildly than they do today.

Source: Business Insider

For example, the temperature in the Arctic Circle soared above freezing for one day in 2016. That's extraordinarily hot for that area, but such abnormalities would start happening a lot more.

Source: Washington Post

If the world were to meet its most ambitious climate-change goals, average winter temperatures in the Arctic will still rise by up to 5 degrees Celsius by the year 2050.

In the summer of 2012, 97% of the Greenland Ice Sheet's surface started to melt. That's typically a once-in-a-century occurrence, but with 2 degrees Celsius of temperature rise, we could see extreme surface melt like that every six years by the end of the century.

Source: Climate Central, National Snow & Ice Data Center

That means years like 2016, which had the lowest sea-ice extent on record, would become more common. Summers in Greenland could become ice-free by 2050.

Source: Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems

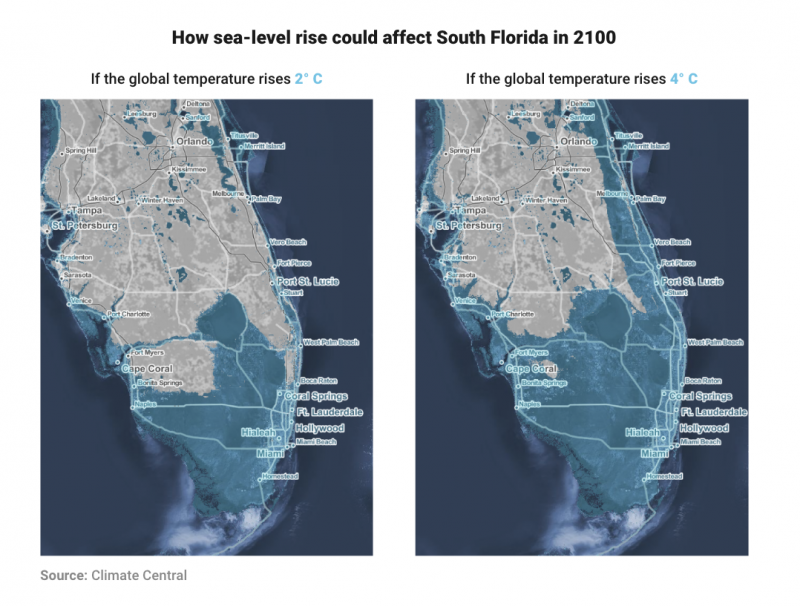

Even in our best-case scenarios, oceans are on track to rise 2 to 3 feet by 2100. This is because water expands as it warms (like most things). That could displace up to 4 million people. (More dire scenarios suggest we'll see up to 300 million refugees by 2050.)

Sources: NASA, Time, The Conversation

The world's coastlines may be unrecognizable by 2100, even with moderate sea-level rise.

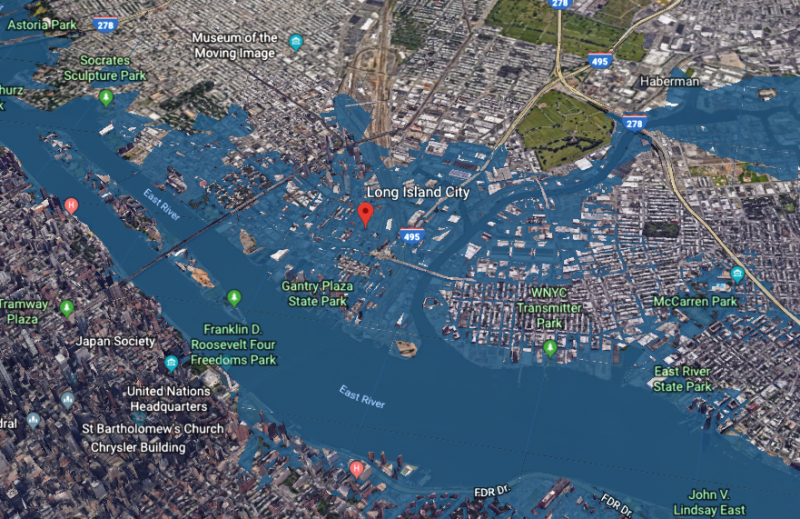

The headquarters that Amazon decided not to build in Long Island City, Queens could have seen regular flooding by 2050. If we blow past the 2 degrees Celsius target, that location could be completely underwater by 2100.

Sources: Business Insider (1, 2)

Sea-level rise threatens coastal flora and fauna, too. Rising waters threaten 233 federally protected animal and plant species in 23 coastal states across the US.

Source: Center for Biological Diversity

About 17% of all the US's threatened and endangered species are vulnerable to rising sea levels and storm surges, including the Hawaiian monk seal and the loggerhead sea turtle.

Source: Center for Biological Diversity

Under our best-case scenario, half of all tropical coral reefs are threatened.

Sources: International Geosphere-Biosphere Program, Business Insider

Other human activities, such as deforestation and logging, could also devastate the planet's flora and fauna species. In roughly 50 years, 1,700 species of amphibians, birds, and mammals will face a higher risk of extinction because their natural habitats are shrinking.

Source: Nature Climate Change

Insects, in particular, are at risk. Scientists found that the total mass of all insects on the planets is decreasing by 2.5% per year. If that trend continues unabated, the Earth may not have any insects at all by the next century. That's a major problem, because pollinators perform a crucial role in fruit, vegetable, and nut production.

Source: Biological Conservation

If that all sounds scary, let's take a look at our worst-case scenario.

If we do nothing to curb greenhouse-gas emissions, roughly 5.3 million more acres are projected to burn each year in the US by 2100. That's an area the size of Massachusetts, and double today's burn rate.

Source: EPA.gov

Without curbing our emissions, the tropics would stay at unusually hot temperatures all summer long. In the temperate zones, 30% or more of the days would have temperatures that we currently consider unusual.

Source: Environmental Research Letters

Even a little bit of warming will likely strain water resources. Left unchecked, climate change may cause severe drought across 40% of all land on the planet — double the amount today.

Source: PNAS

Researchers also worry that if we see more than a 2-degree-Celsius temperature increase, that could tip the balance of our planet's systems toward a "hothouse Earth" scenario. In that case, a feedback loop could lead temperatures to rise by 4 or 5 degrees Celsius.

Sources: Business Insider (1, 2)

The resulting heat from steadily increasing greenhouse-gas emissions could cause stratocumulus clouds to disappear entirely in the next 150 years. Without these clouds, which shade the planet from the sun's rays, the Earth's temperature could rise as much as an additional 8 degrees Celsius.

Unexpected ice-shelf collapses could also surprise us with extra sea-level rise. If warmer water causes the glaciers that hold back ice sheets on top of Antarctica and Greenland to give way, that would cause massive quantities of ice to pour into the world's oceans. This could lead to extremely rapid sea-level rise in an event called "a pulse."

Source: Business Insider

Right now, humanity is on a precipice. If we ignore the warning signs, we could end up with what Schmidt envisions as a "vastly different planet."

Or we can innovate. Many best-case scenarios assume we'll reach negative emissions by 2100 — that is, develop ways to suck carbon dioxide back out of the atmosphere. But those technologies are not a silver bullet.

Source: The Guardian

The world's climate has already changed significantly over the past few decades. But every fraction of a degree of warming that we can avoid in the future will make a difference.